Anti-Corruption

What are the Indian and Chinese governments doing at home to tackle corruption?

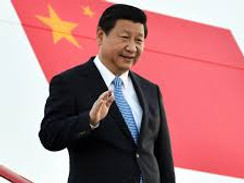

Comparatively, China’s anti-corruption efforts are led by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection since 2017 as part of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption 'Eight Points' campaign that launched in 2013. Prior to this, several different internal state agencies dealt with corruption, such as the Ministry of Supervision which dealt with prevention of corruption; the Discipline Inspection Commission that enforced party guidelines and discipline; the National Audit Office, who were responsible for the inspection of state owned enterprises and government entity accounts; and the National Bureau of Corruption Prevent, which was meant to enhance the transparency of government and coordination of anti-corruption efforts across these different institutions.

In India today, there are three primary regulatory authorities who deal with the monitoring and investigation of corruption and bribery in India. First, the Central Vigilance Commission investigates corruption in central government departments and companies, and local government and public servants. Cases can be referred from the CVC to the Central Bureau of Investigation, who can investigate central government, and Anti-Corruption Bureau, who are empowered to investigate corruption within states. Finally, the Serious Fraud Investigation Office investigates companies, as directed to do so by central government. Cases under investigation by the SFIO are dealt with exclusively by this agency and no others, and also wields more power than the other two authorities, such as power of arrest

Today, under President Xi, the anti-corruption efforts have been much stronger than in India in recent years as the number of officials working in corruption investigations in 2017 increased by 50%, with over 1.31 million complaints being recorded, and 210,000 officials punished for corruption in the first half of 2017 alone . Under Modi, we have seen more anti-corruption laws passed, but the impact of these is hard to determine as the Indian government does not tout their successes as loudly as China. To find out more about the anti-corruption policies passed in both states, take a look below.

Here's a brief guide to the key points in Indian and Chinese anti-corruption campaigns. Scroll down to learn more!

How have the Indian and Chinese governments tried to tackle corruption over the years? Scroll through below to see what major policies were introduced in each state

Internationally, both India and China have made commitments to anti-corruption efforts. China has committed to several conventions to demonstrate their commitment to anti-corruption efforts. Both India and China ratified The United Nations Convention against Corruption (2005), UN Convention on Transnational Organised Crime (2000) (8). India has ratified the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, compared to China who only supported the Working Group on Bribery.

China led the APEC Network of Anti-Corruption Authorities & Law Enforcement Agencies. In 2016, it committed to enhance international anti-corruption cooperation by denying safe haven to individuals and groups involved in corruption; supported information sharing between international communities; signed bilateral treaties on extradition and mutual legal assistance. (Transparency International 2017).

Finally, both are members of the G20 Anti-Corruption Action Group.

Is it working?

Overall, the anti-corruption campaigns in both India and China can be said to suffer from a distinct lack of political will: where the central governments in both states have no real desire to tackle corruption, it therefore continues to run rampant. In India, a lack of political will to tackle corruption is clear given the lack of funding and resources given to anti-corruption agencies. Central government officials often hinder or manipulate investigations by giving agencies enough power to allow for some activity, but not enough to truly be effective in prosecuting individuals or companies [1].Similarly, in China the anti-corruption drive can be argued to be more strategic than about reducing corruption: by removing obstacles within the Party, the higher echelons of the Party are more able to pursue their private goals and therefore continue to engage in informal practices, keeping those in the party elite at the top [2].

In India, the government provides supposedly independent agencies to tackle corruption, but hinders these efforts by restricting powers and interfering, whereas in China, the state controls all anti-corruption agencies and so can inherently influence investigations and cover up abuses of power where they see fit. China lacks an independent judiciary and free press, whereas India has an independent judiciary and press, but does not properly enforce legislation and influences investigations. The lack of singular legal standard in China, owing to a dual system for party officials and citizens, further undermines the potential to effectively tackle corruption as Party Laws are given a higher status than the penal code, allowing those at the top of the Party to apply them at will [2]. This is best summarised by Wang Qishan, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and secretary of the CPC Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI): "Once you join the Party, you have to be beyond reproach in your political stance, be obedient to the Party and act as ordered."

As a result of the lack of political will to actually tackling informal governance practices in India and China, use of anti-corruption campaigns results in a lack of transparent processes, no meaningfully independent investigatory or judicial bodies, and the continuation of informal practices.

References:

-

John S.T. Quah (2008),‘Curbing Corruption in India: An Impossible Dream?’, Asian Journal of Political Science, 16:3, 240-259, Accessed 3.11.2019

-

Osburg, 'Making Business Personal: Corruption, Anti-Corruption, and Elite Networks in Post-Mao China’, Current Anthropology, Volume 59, Supplement 18, April 2018, Accessed 3.11.2019

-

https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=17185ebc-cfd3-4f76-a504-edf12b3361a3

-

https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/09/chinas-anti-corruption-campaign-ensnares-tens-of-thousands-more

-

https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/anti_corruption_changing_china

-

https://www.ft.com/content/2cc4981c-5448-11e4-84c6-00144feab7de?siteedition=intl#axzz3GOaqRCBY

-

John S.T. Quah (2008),‘Curbing Corruption in India: An Impossible Dream?’, Asian Journal of Political Science, 16:3, 240-259, Accessed 3.11.2019

-

http://www.oecd.org/corruption/oecdantibriberyconvention.htm

-