Informal Governance in India

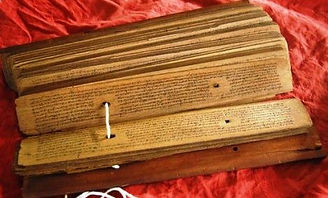

Corruption in India is not a new phenomenon. Two thousand years ago, the Sanskrit philosopher Kautilya wrote Arthashastra, a political treatise detailing the forty ways a king’s beuarocrats were likely to cheat the state of its revenue. Though the informal practices used by political agents have changed dramatically since Kautilya’s times, their influence on agent-principle decision-making has remained substantial.

Corruption is often defined as ‘deviations from the formal rules governing the allocative decisions of public officials’[1]. Post-independence Indian corruption is centered on five main political actors: the neta, the corrupt politician; the babu, the corrupt bureaucrat; the lala, the corrupt businessman; the jhola, the corrupt NGO; and the dada, the criminal of the underworld[2]. To understand how economic liberalization and political decentralization in the nineties changed Indian informal practices, we must first answer the question of what practices were constructed in the post-independence period prior to liberalization.

Nehru’s India: the ‘License-Permit Raj’

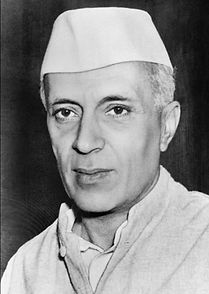

The period between 1951 and 1991 is often dubbed the ‘License-Permit Raj’, referring to ‘a system of central controls introduced in 1951 regulating entry and production activity in the registered manufacturing sector’[1]. India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, based the new regime’s economic policies around the Fabian Socialist ideology. He enacted strict economic regulations to develop the domestic market through Soviet style Five-Year Plans. The 1951 Industries Development and Regulation Act granted the government executive control over business (hence the name ‘License-Permit Raj’); private enterprise was policed, foreign investment was made impossible, and economic competition was constrained significantly.

The ‘License Raj’ failed to lead to economic prosperity. In fact, the World Bank estimated in 1951 that one hundred and sixty four million Indians were living in poverty. By 1991, that number had doubled to three hundred and twelve million.[2] The low levels of economic development and growing levels of income inequality have been largely attributed to corruption.

.jpg)

The government’s strict licensing policies set up barriers to entry for small and new firms[3]. Instead, the government’s executive control over what, who, how much, and where goods were manufactured unintentionally created monopolistic and oligopolistic privileges for the lala (or corrupt businessman) in many industries like cement and textiles. The dominance of family owned firms in the pre-independence era (such as the Tata's and the Ambani's) was strengthened during the Licensing Raj. Political elites, such as the Tata's, used their financial resources and political connections to obtain licenses that were unavailable to smaller firms. The lack of foreign competitors allowed political elites to play the ‘license game’ in a protected environment.

The License-Permit Raj failed to curb corruption because economic centralization had created an imbalance between political and economic opportunities.[4] With the economic agenda heavily centrally controlled, bureaucrats abused their political power to enrich themselves. By selling off state-controlled enterprise and resources to the highest bidders, the babu and the lala created economic opportunities for themselves where there weren’t any for the ordinary Indian.

Rao’s Liberalization: the ‘Tender Raj’

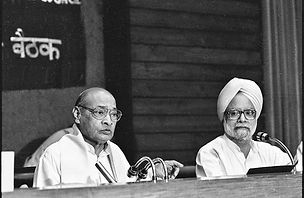

In the same year the USSR collapsed, India ironically launched its ‘New Economic Policy’. The NEP aimed to minimize the influence of the state in the economy in order to integrate India into the global economy.[5] The reforms included industrial reform (including the privatization of public enterprises), trade liberalization, financial sector reform, and fiscal stabilization.[6] Prime Minister Narasimha Rao’s decision to decentralize the economy is largely seen as the end to the ‘License Raj’.

In line with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank’s Washington Consensus, Rao’s liberalization policy was expected to restrict opportunities for systemic corruption. Instead, the relaxation of regulations on economic activity ‘created an era of free-for-all’; bureaucrats, politicians, and big business continued to engage in rent-seeking behaviour[7]. The storm of corruption rackets that followed the 1991 policy – the 1992 securities scam, 1993 Asean Brown Bover scam, the 1995 Jain Halwa scam and telecom scam – is testament to how liberalization empowered corruption to flourish. Measures to reduce corruption since have been equally unsuccessful – India’s Corruption Perception Index ranking dropped ten points between 1998 and 2018[8].

Democracy and the free market did not cure Indian corruption because Rao’s liberalization policies were not introduced in conjunction with new legal and judicial institution that policed conflict of interest, financial enrichment, and bribery effectively.[9] As Tresiman (2000) notes, the existence of effective legal systems raises the stakes of corruption and acts as a deterrent. Where there are low probabilities of prosecution for informal activity, political actors are incentivized to rent-seek.[6] Furthermore, Mauro (1995) argued that ethnic heterogeneity increases corruption. In the Indian context, this can certainly explain why openly corrupt political actors continue to flourish within the system.[10] As voters become more polarized along income or ethnic lines, they are more likely to focus on the representation than on the honesty of government officials. For example, the communal violence of 1992 that led to the demolition of the Babri Masjid – a seismic moment in Indian politics and history – brought the BJP into the limelight as the ‘protectors of Hindu identity politics’ despite their illegal activities.

Though liberalization removed the barriers to entry for small and new firms that existed during the License Raj, allowing 14 of the top 50 Indian businesses at the end of the decade to be first generation businesses[11], it did not create barriers to corruption as hoped. Instead, the lack of regulation and low probability of punishment acted as incentives for political actors to scam the system.

References:

[1] Khan, Mushtaq H. "The efficiency implications of corruption." Journal of International Development 8.5 (1996): 683-696

[2] Agrawal, Arun Kr. "Corruption in historical perspective: a case of India." The Indian Journal of Political Science (2007): 325-336

[1] Philippe Aghion & Robin Burgess & Stephen Redding & F Zilibotti, 2005. "The Unequal Effects of Liberalization: Evidence fromDismantling the License Raj in India," STICERD - Development Economics Papers

[2] Corruption: functional anarchy in governance, Bhure Lal. Siddharth Publications. New Delhi, 2002.

[3] Gollakota, K. and Gupta, V. (2006), "History, ownership forms and corporate governance in India", Journal of Management History, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 185-198.

[4] Sun, Yan, and Michael Johnston. “Does Democracy Check Corruption? Insights from China and India.” Comparative Politics, vol. 42, no. 1, 2009, pp. 1–19. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27822289.

[5] Sengupta, Mitu. “How the State Changed Its Mind: Power, Politics and the Origins of India's Market Reforms.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 21, 2008, pp. 35–42.

[6] Ghosh, Arun. “Who's Afraid of Liberalisation?” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 30, no. 1, 1995, pp. 12–14.

[7] Banerjee, Sumanta. “Better 'Nouveau' than Never.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 38, no. 49, 2003, pp. 5145–5146.

[8] Transparency International. “Corruption Perceptions Index 1998.” Research - CPI - Corruption Perceptions Index 1998, www.transparency.org/research/cpi/cpi_1998/0; e.V., Transparency International. “Corruption Perceptions Index 2018.” Www.transparency.org, www.transparency.org/cpi2018.

[9] Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 2008. “Democracy and ‘Grand’ Corruption,” International Social Science Journal, 48(149): 365-380.

[10] Treisman, Daniel. 2000. “The Causes of Corruption: A Cross-National Study,” Journal of Public Economics, 76(3): 399-458.

[11] Mauro, Paul. “Corruption and Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1995 (110: August), 681–712

The Kautilya

Prime Minister Nehru

JRD Tata, leader of the Tata Group prior to liberalisation

Narisimha Rao unveiling the Liberalisation policy in 1991

Prime Minister Narasimha Rao