Informal Governance in China

Context

"The party is at risk of failure unless we punish corruption, especially corruption at the high levels of the party"

Deng Xiaopin

"If we do not firmly punish corruption, the flesh-and-blood ties between the party and the masses would be ruined, the party would be in danger of losing its ruling status and the party would suffer self-destruction"

Jiang Zemin

"To further promote anti-corruption efforts, we need to insist on the successful experiences gained through the Party’s long-term anti-corruption practice. We need to actively draw on effective practices conducted by foreign countries around the world, and our own valuable heritage"

Xi Jinping

This is perhaps motivated by the visibility of how those in power also possess immense wealth. For example, the wealthiest 70 delegates to the National People's Congress had a net worth of approximately $90B [1]. While in another emerging country of similar size, India, the delegates to the Indian Parliament only have $0.5B in assets. Since the legitimacy of the political system is not based on elections, but on meritocracy - the selection of leaders based on their ability and virtues - the level of corruption can potentially erode the people's faith in their leaders, hence, threaten the party and the political system as a whole [2].

From the quotes above, we can see that Chinese leaders for the past three generations have viewed the issue of corruption with increased caution - seeing the increased incidence of corruption as a direct threat to the legitimacy of the current political system in place.

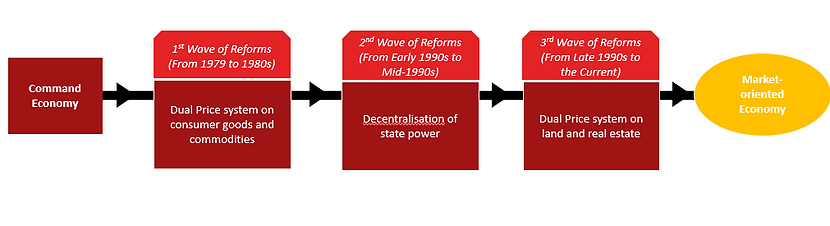

Apart from that, China is also a special case study - contrary to academic arguments that high levels of corruption stunts economic growth - in China, economic development and corruption have shown a positive correlation. We can trace this uptick in dramatic economic growth and corruption in waves with respect to different stages of economic liberalisation: Post-Mao economic reforms were initiated at the end of the 1970s, and it brought about waves of reforms that transformed the previously command economy (where the government takes up the role of central planning to attain its social goals) into a market economy (which allows for market forces to determine production and prices).

Waves of Economic Reform

And the Associated Structural Opportunities for Corruption

China took a gradual approach in converting its command economy to a mixed economic system, each wave of economic reform opened up associated structural opportunities for corruption. This page catergorises the state induced economic reforms into three waves and describes the corrupt behaviour commonly seen during these periods.

1st Wave of reforms (From 1979 to 1980s) - Dual price system in consumer goods and commodities

In the 80s, while maintaining the fundamentals of a planned economy, the government gradually allowed local officials and manufacturers to take part in the production process. Under the dual track system, the economy had characteristics of both a market oriented and planned economy, and products have 2 prices: one that was controlled by the state, and the other at the market price [3]; but the state officials had the power to demand a specific price for a product. This gave rise to "rent-seeking" behaviour as businesses that wanted to maximise their profits were motivated to bribe officials and the state officials could exploit the price differentials for personal gains. For example, a colour television was sold at US$1,200 at market price but for US$600 in state-owned consumer stores [4].

2nd wave of reforms (From Early 1990s to Mid-1990s) - Decentralisation and the rise in power of local authorities

China pursued a vertical decentralisation of state power, distributing its power to local level governments. All of these newly obtained powers gave officials more control and opened doors for rent-seeking behaviour - local state officials could determine local taxes, budget allocation, fee structures and construction approvals. There were two main types of corruption during this wave:

1) to obtain insider information on financial institutions, construction, transportation for personal gains.

2) to bribe officials for tax reliefs and official approvals for private projects.

According to the Supreme Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China’s Annual Report, 2.2 billion Yuan was involved in corruption in 1993, which also led to the prosecution of over a 1000 high level officials [4].

3rd wave of reforms (Late 1990s to now) - Dual price system on land and real estate

Land is the single most valuable state-controlled asset and has become a major target for corruption. Prior to the reforms, land was a part of state property and could not be owned by businesses and individuals. However, the relatively more market oriented economy allowed for different types of ownership: state-owned, semi-state-owned and private owned firms. State officials frequently abused their power to obtain from farmers at market prices (very low prices) and sell them to developers. Total of 157,958 cases of land law violations that involved 26,925 hectres of land [5].

Role of Quan-xi Practices

[1] Zúñiga, Nieves (2018). "CHINA: OVERVIEW OF CORRUPTION AND ANTICORRUPTION" Anti-Corruption Help desk, Transparency International

[2] Deng, Xiaogang (2010). "Official Corruption During China’s Economic Transition: Historical Patterns, Characteristics, and Government Reactions" Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 26(1) 72-88

[3] Zhan, Jing Vivian (2012), "Filling the gap of formal institutions: The effects of Guanxi network on corruption in reform-era China" Crime Law and Social Change, 58 (2)

[4] Deng, Xiaogang (2010). "Official Corruption During China’s Economic Transition: Historical Patterns, Characteristics, and [3]Government Reactions" Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 26(1) 72-88

Supreme Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China. (n.d.). Supreme Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China’s Annual Report from 1988 to 2018

[5] Yu, O. (2008). Corruption in China's economic reform: a review of recent observations and explanations," Crime, Law and Social Change, 50(3), 161176

What is Guan-xi?

Guanxi-practices is a particular form of social network that is common in China and other East and Southeast Asian societies that are heavily influenced by the Confucian culture. This type of social network also shares similarities with the social networks prevalent in other cultures, such as blat in Russia [1]. Guan-xi practices is deeply rooted in the Chinese cultural traditions on social relationships and the ethics of reciprocity; people within a guan-xi network usually have a strong sense of personalism and have a strong reciprocal tie, and such ties are built from a prolonged period of exchanges of gifts and favours. While favours and gifts are not paid off immediately, each interaction and transaction can further consolidate the existing guan-xi between the two actors and set the precedent for reciprocation in the future [2].

Due to the illegality of corruption and the negative sentiment towards it amplified under Xi's anti-corruption campaign, practitioners resort to alternative operating mechanisms in order to break down the legal, moral and cognitive barriers that hinder the corrupt transaction. Mechanisms such as guan-xi practices exploit the structural opportunities created with each wave of economic reforms. This page includes a description of the operation of guan-xi practices and the barriers it breaks to foster corruption.

What is Guan-xi?

Guanxi-practices is a particular form of social network that is common in China and other East and Southeast Asian societies that are heavily influenced by the Confucian culture. This type of social network also shares similarities with the social networks prevalent in other cultures, such as blat in Russia [6]. Guan-xi practices is deeply rooted in the Chinese cultural traditions on social relationships and the ethics of reciprocity; people within a guan-xi network usually have a strong sense of personalism and have a strong reciprocal tie, and such ties are built from a prolonged period of exchanges of gifts and favours. While favours and gifts are not paid off immediately, each interaction and transaction can further consolidate the existing guan-xi between the two actors and set the precedent for reciprocation in the future [7].

During the transitional reform era, individuals gradually became more aware of public ethics as the Communist Party adopted a harder official political narrative against corruption, bribed faces a more severe legal sanction than before, and the sentiments of moral repugnance and censure towards corruption became more apparent. Guan-xi practice is a trust-building process that attempts to remove the legal and moral & cognitive barriers of corruption:

Legal Barrier:

Experienced bribers can conscientiously control the contracting process and intentionally allow for a time lapse between the initial gift and when the favour is returned. With a chronological distance between gift-giving/taking and the delivery of the corrupt service, the parties can avoid the label of a corrupt exchange and instead classify it as an exchange of favours [8]

Moral and cognitive barriers:

Bribers can substitute a context in which a gift would otherwise be prohibited by formal rules with a context in which acceptance of a gift is both conventional and expected. An unlawful act of bribery can be transformed into one that is seen as an act of kindness, care and understanding. [9]

Contrary to a view held by many, it is not that the individuals are compelled to participate in a corrupt exchange due to the existence of a cultural obligation of reciprocity; on the contrary, these participants utilise guan-xi practice as an enabling operating mechanism that exploits structural opportunities during the reform era and facilitates corruption. It provides a "human" interface during the exchange that helps overcome the legal and moral & cognitive barriers.

[6] Zhang, L., & Deng, X. 1998. The effects of structural changes in community and work unit on crime in China. In Li Xiaobing & Zhang Jie (Eds.), The social transition in China, (pp. 133- 154)

[7] Sun, Y. (2004). Corruption and market in contemporary China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

[8] Ling Li (2011) Performing Bribery in China: guanxi-practice, corruption with a human face, Journal of Contemporary China, 20:68, pp 17

[9] Ling Li (2011) Performing Bribery in China: guanxi-practice, corruption with a human face, Journal of Contemporary China, 20:68, pp 19